I ranked all the second season episodes of Community to demonstrate how consistently good it was this year. I’m ranking all the sixth season episodes of How I Met Your Mother for a somewhat different reason.

After a poor fifth season, HIMYM desperately needed a comeback. And for the most part it had one. It started off solid, but inconsistent, only to rattle off a string of very strong episodes in the middle of the season. Unfortunately, it completely fell apart at the end, and that’s likely to be the thing fans and critics remember heading into next year. Which is a shame, because HIMYM produced an awful lot of good episodes this season, and at least a couple classics. To wit, the list:

24. The Exploding Meatball Sub: An unmitigated disaster. There are elements of “The Exploding Meatball Sub” that could be funny and elements that could be touching, but the writers ruin them all by playing them against each other in such a way that not only undermines the emotional impact of the episode, but also of the whole season. This is the episode that completely reverses the show’s upward momentum and leads into a final stretch of episodes that more or less destroys the season’s reputation. Given its impact on the season and the future of the show as a whole, I would consider this the worst episode of the series.

23. Challenge Accepted: There are some decent beats toward the end–Lily’s pregnancy, Barney and Robin’s conversation in the taxi, Barney’s future wedding–but mostly “Challenge Accepted” just didn’t feel like a finale at time when the show desperately needed to show some sense of focus.

22. Landmarks: The penultimate episode of the season focuses squarely on the end of Ted and Zoey’s relationship, which is a glorious thing. Actually watching it, however, isn’t, as both Zoey and Ted are just terrible, terrible human beings.

21. Canning Randy: Will Forte’s character has always been too broad by half, and that’s the case here as well. Much more disturbing, however, is the humiliation the episode heaps upon Robin, whose arc has gone in some pretty problematic directions in general. The reveal at the end here–in which we discover that Robin has played a sexy nurse in an adult diaper commercial–is frankly inexcusable.

20. Unfinished: There’s a heavy focus on Robin’s fifth season boyfriend Don in this episode. And that’s basically all you need to know about it.

19. The Perfect Cocktail: The cocktail device is fun, but the narrative at this point in the season–all about Ted, Zoey and The Arcadian–had completely lost me. The cockamouse deserves better.

18. Architect of Destruction: This episode features a lot of dick jokes and the introduction of Zoey. The dick jokes are sporadically funny. Zoey, however, is the destroyer of all things good and holy. Her awfulness far outweighs even the best of the penis humor.

17. Oh Honey: HIMYM first became a genuine hit when they stunt cast Britney Spears back in season 3. “Oh Honey” feels like an attempt to recapture some of that ratings magic. It didn’t really work, but the episode’s funny enough, and Katy Perry’s giant eyes do a decent enough simulating naivety to make her seem passable as an actress.

16. Baby Talk: Like “Oh Honey,” “Baby Talk” is a silly, funny episode. How much better would the season have been if Ted had stayed with this attractive, infantile blonde instead pursuing the other attractive, infantile blonde that featured so heavily this year? It also further establishes Marshall’s relationship with his father, which becomes important later on.

15. The Mermaid Theory: The best thing by far about the Ted-Zoey relationship was Kyle MacLachlan’s The Captain, who features prominently here. Throw in some classic HIMYM unreliable narration and Robin in a manatee costume, and what’s not to like?

14. Garbage Island: People should start shipping Ted and The Captain. They would make a much better couple than Ted and Zoey. Also, Barney meets Nora. And he likes her. Like likes likes her.

13. Subway Wars: One of the show’s occasional New York centric episodes, full subways and taxis and Woody Allen references. These episodes are generally good–as is this one–so it’s odd the writers don’t do them more often.

12. Big Days: A strong premiere that’s exactly what the show needed after a poor fifth season. “Big Days” also blesses us with the presence of Rachel Bilson.

11. A Change of Heart: Barney lies to Nora about what he wants out of their relationship. Or does he? The subplot about Robin’s dog–like boyfriend is stupid, but funny.

10. Hopeless: The return of John Lithgow temporarily gives hope after the disaster that was “The Exploding Meatball Sub,” but the episode title proves an all too apt descriptor for the remainder of the season.

9. False Positive: Built around Marshall and Lily thinking they’re pregnant when they are in fact not, “False Positive” takes the opportunity to send Robin’s character arc in something like a positive direction, even if it does undersell the benefits of being Alex Trebek’s coin flip bimbo. The game show parody is spot-on, and Barney’s Oprah impression is, if nothing else, impassioned.

8. Cleaning House: Ben Vereen guest stars. He’s not Barney’s dad, but he’s really nice about it. Wayne Brady continues to be improbably bearable. Robin sets Ted up on blind date with a women to whom she suggests Ted isn’t awful. This understandably puts Ted under a lot of pressure to be something other than awful, as that is of course his natural state.

7. Desperation Day: Marshall reverting to a child in the wake of his father’s death is funny, but it also feels very real.

6. Last Words: Mining laughs from funerals while still maintaining the emotional stakes seems like a difficult line to walk, but “Last Words” pretty much nails it. If I were the one in charge of handing out Emmys (and I really ought to be), I’d give Jason Segel two, just for that last scene alone.

5. Glitter: The return of Robin Sparkles. “Glitter” isn’t a very deep episode, but it’s almost preternaturally funny. And sometimes that’s enough.

4. Blitzgiving: HIMYM is always good at Thanksgiving episodes (even after all these years, “Slapsgiving” remains the series high point), and this is no exception, featuring a great guest turn from Jorge Garcia as the unluckiest person in the world. Again.

3. Natural History: The episode that kicks off the great middle section of the season and seemed to announce that, yes, HIMYM really was back. “Natural History” does all the things a really good episode of HIMYM does, and does them well. Even Zoey is bearable. And Neil Patrick Harris completely sells the last scene, when Barney finally discovers the identity of his father.

2. Bad News: Not everyone likes this episode. Not everyone thinks the plots are funny. Not everyone thinks the countdown is a good idea. Not everyone thinks the ending is earned. But they’re wrong. Barney’s doppelgänger is consistently amusing, and though Robin’s story is slight, it’s funny and it brings back Alexis Denisof’s always welcome Sandy Rivers. The countdown has drawn a lot of ire, but I think it perfectly demonstrates the way the moments leading up the most important or tragic events in our life feel. Nothing particularly significant happens throughout the majority of the episode, but they gain significance precisely because they are part of the countdown to the death of Marshall’s father. And even if you don’t buy that–which you should–the final scene is still absolutely devastating.

1. Legendaddy: This is a such a great episode of television that it’s hard to believe the show would completely fall apart immediately afterward. Most unfortunately, that collapse makes it all too easy to forget just how great “Legendaddy” is, easily one of the best five episodes of the series and one of the best episodes of television this year. Lithgow is perfectly cast, and his portrayal of the square, middle-class suburban Dad trying to make up for the biggest mistake he ever made is Emmy-worthy. Segel has yet another great moment, convincing Barney to go have dinner with his father. And Harris does what Harris always does and absolutely owns his showcase episode. “Legendaddy” is about the gaps in our lives, the things that we’re somehow missing, be they a word you can’t pronounce, a basketball hoop over a garage, a father you’ve just lost or a father you’ve never known. And it reminds us that HIMYM can still be one of the best shows on television when it really puts its mind to it.

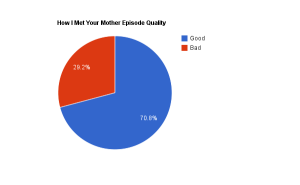

Clearly, the sixth season of HIMYM is not the second season of Community. But on an episode by episode basis, this really is a pretty good season of television. Seventeen out of the 24 episodes are what I would consider good. Here’s a pie chart, because pie charts are awesome:

That’s not a great ratio (Community’s chart would be all blue), but I don’t think it’s an especially bad one either, especially for a show that has always struggled with inconsistency.

That’s not a great ratio (Community’s chart would be all blue), but I don’t think it’s an especially bad one either, especially for a show that has always struggled with inconsistency.

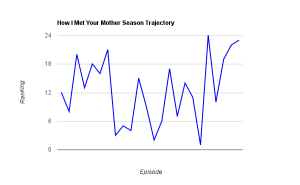

The season’s trajectory is more problematic, however.

Keeping in mind that everything below the 18 marker is pretty good, it’s clear that the season started off solid but inconsistent, and then settled into a prolonged stretch of excellence where it really appeared that the show had turned itself around. If the season had ended with “Legendaddy,” I think we’d all be feeling pretty good about the season and about the show going forward. Instead, five more episodes followed, four of which were subpar to awful and focused on plots that were of interest to nobody. Further, the final five episodes aired after a long break, creating a distance from the season’s good stretch that made it all too easy to forget about. As a result, the perception of the season as a whole has suffered, and it will likely make fans and critics less charitable going forward.

Keeping in mind that everything below the 18 marker is pretty good, it’s clear that the season started off solid but inconsistent, and then settled into a prolonged stretch of excellence where it really appeared that the show had turned itself around. If the season had ended with “Legendaddy,” I think we’d all be feeling pretty good about the season and about the show going forward. Instead, five more episodes followed, four of which were subpar to awful and focused on plots that were of interest to nobody. Further, the final five episodes aired after a long break, creating a distance from the season’s good stretch that made it all too easy to forget about. As a result, the perception of the season as a whole has suffered, and it will likely make fans and critics less charitable going forward.

The real question, though, is whether that great middle stretch of episodes is something HIMYM can repeat or whether we’re doomed to more and more episodes like “Landmarks” and “The Exploding Meatball Sub.”